Essential Question: What was the experience like for a U.S. soldier during the Meuse-Argonne campaign?

The Argonne Forest loomed as an impenetrable fortress to the east of a landscape of rolling fields with small hills and heights, bordered by the Meuse River to the west. When thinking of a forest, one might expect dense vegetation, poor visibility, and a generally difficult position to attack. The Argonne proved more than just a forest. Its uneven ground, sharp cliffs, ravines, and streams were a barrier that would require fierce fighting to wrest from the entrenched Germans. However, once past this barrier, the American Army could continue to roll through northern France to the borders of Belgium and Luxembourg.

One of the instrumental divisions in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the 77th Division, sometimes referred to as the Statue of Liberty Division, as it was composed mostly of soldiers from New York City. These men, from varied ethnic backgrounds, represented the diverse culture of urban America at the turn of the century. Mixed in with the New Yorkers were some soldiers from Montana and Wyoming, farm boys. At first, the men took pride in their differences; however, when separated in a ravine in the Argonne Forest for five days, they learned to work together to survive and maintain their position.

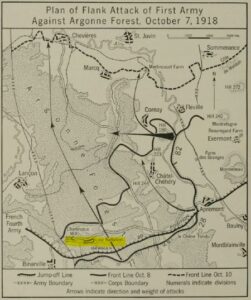

On September 26, the First Army ordered the 77th Division to advance through the Argonne Forest, with the goal of regaining control of the area as a jumping-off point to penetrate the other German lines. Additional American troops, joined by the French, proceeded to drive north through the Aire Valley, attacking into the Champagne region of France. The Germans, however, held the heights of Romagne, Cunel, Montfaucon, and the heights above the Meuse River, allowing them to inflict heavy losses on the advancing Allied troops. The Americans had plenty of spirit and courage, but they lacked training and experience. Most reinforcements in the region were recent draftees, and some had never fired a gun or seen a grenade.

Like the rest of the American commanders, Major Charles White Whittlesey’s First Battalion, 308th Regiment, faced the same inexperience. Whittlesey, a Harvard-trained attorney, had been practicing banking law in New York City before the war [i]. His troops, like himself, were unprepared for the stress and trauma of war, and his veterans were exhausted. However, they pushed forward.

At 6 a.m. on October 1, 1918, Whittlesey’s First Battalion pushed forward through thick brush, tangled wire, abandoned German headquarters, and fields littered with dead bodies, all while under constant fire from German snipers and machine guns.

Their objective was a ridge north of the Charlevaux Mill Road [ii]. As the unit advanced, they found themselves in a wooded ravine, surrounded by hostile Germans by the evening of October 2 [iv]. They dug into the side of the ravine and waited for reinforcements, enduring hunger, thirst, and dwindling ammunition.

Whittlesey relied on runners to communicate with command, but they quickly fell victim to enemy fire. With no other options, he used carrier pigeons to deliver messages for reinforcements [vi]. Meanwhile, the men endured relentless German attacks, while food and water supplies ran dangerously low. By October 3, twenty-five percent of the battalion had become casualties, and they had no medical supplies to treat the wounded [ix]. Despite this, they refused to surrender or abandon their position.

On October 4, American artillery mistakenly began shelling the Lost Battalion’s position. In desperation, Whittlesey sent his last pigeon, Cher Ami, with a message: “Our artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For Heaven’s sake, stop it” [xiv]. The barrage ceased at 4:20 p.m., saving the remaining troops.

On October 8, reinforcements finally reached Whittlesey’s unit. Of the more than 600 men trapped in the ravine, only 190 walked out, while 190 were wounded, 110 were dead, and 60 were missing [xv]. Despite its tragic losses, the Lost Battalion’s resilience became a symbol of American endurance and determination.

References

[i] Robert. J. Laplander, Finding the Lost Battalion (Wisconsin: American Expeditionary Foundation, 2007), 42.

[ii] Edward Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918 (New York: Holt, 2007), 223.

[iii] Lengel, 224.

[iv] American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe (Washington, DC.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1995), 337.

[v] Lengel, To Conquer Hell, 226.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid., 230.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., 231.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] James B. Legg, “Siege in the Argonne.” Legacy 17, no. 1 (2013): 15-15, 15

Instructional Activity: Primary source work with excerpts found in Laplander’s book.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.